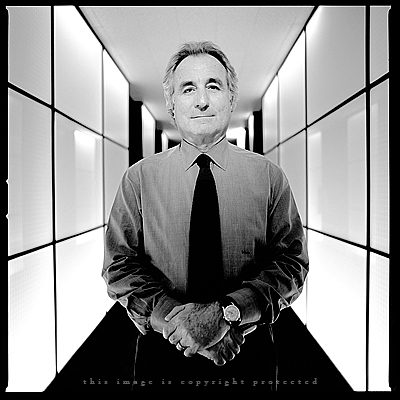

A friend suggests that my recent arguments against the moral status of contempt ignored an important role it plays in policing our moral community. The concern is that if we cannot feel (and expect others to feel) contempt for someone like Bernie Madoff, then we will lose the morally instructive value of punishment. If we wish to live in a culture that does not encourage people to take advantage of each other, we must collectively judge cheaters and frauds as morally ‘less worthy’ than non-cheaters and non-frauds. My friend claims that we are all better than Bernie Madoff, and a failure to feel contempt for him would itself be a mistake or error in judgment.

A friend suggests that my recent arguments against the moral status of contempt ignored an important role it plays in policing our moral community. The concern is that if we cannot feel (and expect others to feel) contempt for someone like Bernie Madoff, then we will lose the morally instructive value of punishment. If we wish to live in a culture that does not encourage people to take advantage of each other, we must collectively judge cheaters and frauds as morally ‘less worthy’ than non-cheaters and non-frauds. My friend claims that we are all better than Bernie Madoff, and a failure to feel contempt for him would itself be a mistake or error in judgment.

I think this is the heart of the dispute over the value of contempt: proponents of contempt can certainly agree that contempt is often misused, that it short-circuits dialog and even often disguises itself as legitimate when it is not. However, they want to say, contempt can be appropriate. We may disagree on when exactly it is warranted, but we can come to an agreement with enough dialog, and perhaps we ought to do so.

This reminds me of Arendt’s account of Adolf Eichmann in Eichmann in Jerusalem. Arendt presented Eichmann in such a compassionate and understanding light that many people thought she was trying to exonerate him. Yet at the conclusion she makes it clear that we cannot share the world with men who have acted as Eichmann acted. At times she calls him a buffoon, but only as a corrective to those who would call him a monster. And she always maintains that he deserved a fairer trial than he received and a better defense, not because he was innocent, but because he was of equal moral status with any other person. Without contempt, she still managed to condemn him. In this, I think we see the difference between what Jonathan Haidt calls moral intuitions of ‘hierarchy’ and moral intuitions of ‘fairness’. Arendt’s attempts to understand Eichmann and to overcome the emotive response to him never undermined her capacity to condemn. We condemn an action for the injustice or lack of care that it demonstrates, and as a result we condemn a person to a punishment. Yet when we feel contempt, that emotion purports to bear on the person’s moral status, not her just deserts.

Another interesting question is what this tells us about deference and respect. If contempt is immoral, should we say the same thing of deference? This objection seems to confirm that contempt is superfluous to moral judgments, that it masquerades as valuable by disguising itself as necessary for them. In this disguise, we see that status emotions seem parasitic on emotions related to justice and care: the non-moral emotions feed on our moral emotions in the name of our desire for status and deference. When we feel contempt for Madoff, we imagine ourselves as having at least one more person in the world who would have to respect us, if ever we met. Madoff or Eichmann serve as imagined objects of our domination: they bolster our self-image through imagined recognition. Rich as he was, old Bernie Madoff owes me deference because he is a crook and I am not. Yet notice that I am not really any better a person than I was before Madoff was caught and convicted. So in this way, again, contempt lies to us. It tells us we are better only because others are worse… yet I do not become a better runner because others are crippled.

Leave a Reply