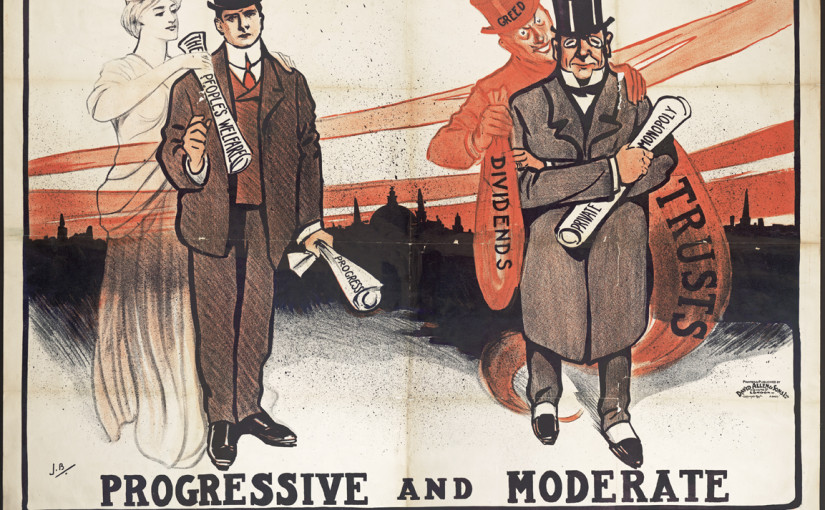

One of things I like least about elections is partisanship. This is a strange thing to say, since of course if an election is to occur, it should be about differences in the candidates’ policy preferences and at the national level most voters must use political parties to get a clear sense of how the candidates would act in concert with other elected politicians.

In that sense, we seem to be getting much better at distinguishing our choices. Only a few generations ago, political scientists protested the lack of significant differences between the parties. They could hardly do so today: the last two decades have been a time of serious and growing polarization and enmity. Yet it seems we are rancorous on almost every question, from health care and same sex marriage to climate change policy and gun ownership. No gag rule can prevent the partisan spin that takes new issues and renders them fodder for our passionate disagreements. In that context, the most successful political activism will be sub-national or international: it will ignore the national institutions designated for politics but riven by paralysis.

But one of the things that I think I know is that no matter how much we might disagree about one law or policy, that disagreement should not be allowed to destroy the possibility of a future alliance on a different problem. Citizens tempted by partisanship have to find a way to hold their ideas and convictions loosely. They have to preserve civic friendship and reject permanent divisions. In a society where a few issues become the signal issues of note, our enmity grows until it encompasses every other issue where we might share interests. Thus, deep partisanship is paralyzing not just because it comes from real intractable disagreements, but because those intractable disagreements radiate out into the rest of our civic lives.

Thus a good society will tend to suppress those areas of passionate disagreement in favor of the alliances and collaboration that less contentious matters make possible. The trick is that areas of passionate disagreement tend to be pretty important. Consider Stephen Holmes’ Passions and Constraint: On the Theory of a Liberal Democracy, where Holmes points out how often the liberal order has survived in the US by creating a political system that deliberately ignores the most pressing and passionate politics of the day. After all, the republic was founded to preserve slavery and ignore the very pressing arguments against it. Holmes even recounts the brutal beating of Senator Charles Sumner by the coward Albert Brooks in a discussion of the Senate’s tacit gag rule on discussions of slavery. For this reason, Holmes praises the liberal and undemocratic institutions like the Supreme Court that can dissolve passionate disagreements without invoking the brutal passions of citizens who must find a way to work together the next day.

This is moderation: a position every bit as as compromised at the example of anetebellum Senators standing by the beating of an abolitionist by a slave owner, along with ignoring the enslavement of their fellow human beings. The things we feel most deeply, including the evils in which we reject complicity, are not things we should ignore. Indeed, we should see opponents who support such acts and policies as irredeemable, evil, monstrous; not fellow citizens and sometimes allies but perpetual enemies. We should reject compromise with such people until the battle is won.

But here’s the problem: they think the same thing. And there are systemic facts about our political constitution that will always work to create partisan identities of roughly equal size in our national political life. Most arguments in Congress are tied to changes in spending and taxation that amount to a few points of GDP either way. Most radical conservatives and radical liberals actually hold a group of varied and contradictory beliefs, very few of which fit into this frame of enmity and hatred. So terms like Republican and Democrat and conservative and liberal are free-floating signifiers that don’t really track particular policy preferences or ideologies over time, even as they mark a long-term division among those who ought properly to concern themselves with the co-creation of our shared world.

Almost all of the things we think about politics, especially about the other party, just aren’t true.

Here’s what’s true, to the best of my knowledge:

There are real differences between the parties. But they’re not nearly as big as the parties and their adherents like to pretend, even as the parties have grown a lot more polarized (which is to say, the differences used to be even smaller!) One of these parties is not communist, and the other party is not libertarian. At most, Democrats want to raise federal spending by a few points of GDP. At most, Republicans want to cut federal spending by a few points of GDP.

African-Americans are still killed and incarcerated in large numbers by cops in Democratic cities. Women are still raped and abused in Democratic strongholds. The things that matter most to these groups are very rarely even on the ballot or in front of the relevant politician: the one exception is abortion, and in the states where it’s on the ballot, women (50% of whom think abortion is morally wrong) are voting against it too.

Political radicalism among our representatives is mostly drive by: (1) the way that we have sorted ourselves into partisan enclaves, (2) the way the primary system has changed, (3) and the strong restrictions on “pork” which used to grease the skids of bipartisanship. (4: Campaign Finance issues matter, too.)

There are many questions about whether the electorate has changed as well, but the best evidence suggests that we’re just as mixed up ideologically as we always were: as an empirical matter, ordinary Americans do not use these abstract terms in the same way partisan intellectuals do. Self-classified liberals tend to have liberal views on specific policy issues, but self-classified conservatives are much more heterogeneous; many, even majorities, express liberal views on specific issues, such as abortion rights, gun control and drug law reform.

That is, the supposed polarization of the electorate is just as much a myth as any supposed moderation. It’s probably more sensible to say that we’re all over the place, radically liberal and conservative and sometimes moderate too: citizens often support policies on both sides of the ideological spectrum, but these policies are often not moderate.

What’s more, President Obama has largely left Bush-era foreign policy in place.

The one place where the parties’ policies and practices really diverge is LGBT rights. And that’s only recently: remember that it was Clinton who signed the Defense of Marriage Act, and the divergence is not going to last for long.

Second Opinions