Forman’s argument is sometimes conflated with that of Naomi Murakawa, who argued that it was liberals, not conservatives, who created mass incarceration by emphasizing the importance of safety over all other civil rights goals. According to Murakawa, when Lyndon Johnson championed the the 1968 Safe Streets Act which swelled the flow of federal dollars–and federally procured military equipment–into local law enforcement, it wasn’t just a capitulation to conservatives, but:

“part of a long-term liberal agenda, one that reflected a belief that federally subsidized police recruitment and training could become racially fair.” (73)

That is, according to Murakawa, Democrats didn’t adopt law-and-order rhetoric to respond to the policy entrepreneurship from Republicans that threatened to swamp them–they explicitly preferred more coercive and punitive state institutions so long as the men and women wielding the riot gear were racially diverse. By the mid-nineties, Bill Clinton wasn’t passing the 1994 Crime Bill because he got dragged there by Republicans, the Democrats lead the way–in fact the Senate version was sponsored by none other than Joe Biden. Murakawa’s conclusion is damning:

In the end, the Big House may serve racial conservativism, but it was built on the rock of racial liberalism. Liberal law-and-order promised to deliver freedom from racial violence by way of the civil rights carceral state, with professionalized police and prison guards less likely to provoke Watts and Attica. Despite all their differences, Truman’s first essential right of 1947, Johnson’s police professionalization, Kennedy’s sentencing reform, and even Biden’s death penalty proposals landed on a shared metric: criminal justice was racially fair to the extent that it ushered each individual through an ordered, rights-laden machine. Routinized administration of race-neutral laws would mean that racial disparate outcomes would be seen, if at all, as individually particularized and therefore not racially motivated.” (151)

James Forman’s book is quite different. Where Murakawa places most of the blame squarely on white Democrats, Forman places his lens on Black politicians in DC, and finds a very different dynamic. From the start, the story of the rise of racialized mass incarceration is a tragic story of reasonable and well-intentioned Black leaders fighting white supremacy and Black disadvantage with reason and evidence. They made deliberate choices that were well-justified and supported by their constituents. And incrementally, they made things worse.

DC’s leaders saw drugs like heroin as a scourge and heroin dealers as race traitors. They saw violent crime rising, and guns playing a major role. And they wanted Black police–because those were good jobs and because Black police officers wouldn’t be tempted to engage in racist practices. So they punished drug dealers and ultimately drug users. They punished violent crime and gun possession. And they did it with a Black-led and majority-Black police force. But still they ended up creating a majority Black prison population in our (I live in DC too) Black-led and Black-staffed prisons and jails.

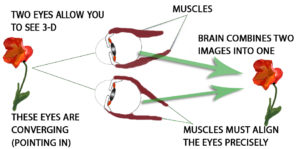

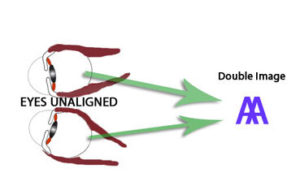

Forman does the hardest thing in criminology and law: he adopts the stereoscopic vision that can see both from the perspective of those who fear crime and those who bear the costs of policing and prisons.* Black District residents know what it’s like to fear that their family and neighbors will fall into drug addiction or be the victims of gun crime. They also know what it’s like to fear that their family and neighbors will be terrorized by the police or have their lives derailed by imprisonment. And Forman is able to square those stories: see the victim’s fear and rage with one eye and the perpetrator’s circumstances and his community’s losses with the other. Alone, either perspective gives a flat, two-dimensional image, but together you get depth: three-dimensions of a wicked problem where values are always at stake but a way forward is possible.

Forman does the hardest thing in criminology and law: he adopts the stereoscopic vision that can see both from the perspective of those who fear crime and those who bear the costs of policing and prisons.* Black District residents know what it’s like to fear that their family and neighbors will fall into drug addiction or be the victims of gun crime. They also know what it’s like to fear that their family and neighbors will be terrorized by the police or have their lives derailed by imprisonment. And Forman is able to square those stories: see the victim’s fear and rage with one eye and the perpetrator’s circumstances and his community’s losses with the other. Alone, either perspective gives a flat, two-dimensional image, but together you get depth: three-dimensions of a wicked problem where values are always at stake but a way forward is possible.

The difference between Forman and Murakawa is that where Forman wants to tell a careful story about wicked problems and their double-binds, Murakawa seems to want to show up liberals (including Black liberal elites) as self-undermining and doomed to failure. This is Afropessimism at its best and worst: any efforts at racial equity are perverse and doomed to failure. I find such arguments deeply challenging when they come from non-white authors, which is why it’s important to me to think seriously about what a perversity argument is doing.

A perversity argument is any argument that claims that when we try to do a thing we believe is important, we will fail and make it worse, falling further behind as we try to move ahead. The actual use of perversity and unintended consequences arguments are often justified by some of the available evidence, as well as some of the speculative hypotheses: try to make someone love you and they will feel manipulated; create a minimum wage to help the poor and you’ll increase unemployment; try to reform the criminal justice system and you’ll just make it stronger and more pervasive; tell someone they’re wrong and they’ll sink even deeper into their error; try to engage in affirmative action to reverse racial discrimination and you’ll entrench stereotypes of inferiority.

Margo Schlanger’s 2015 review of Murakawa’s The First Civil Right has stuck with me for a while in part because I still occasionally hear people pushing the Murakawa line that Democrats and liberals are primarily responsible for mass incarceration, and thus can’t be trusted to reverse it. Schlanger has a great reading of Albert Hirschman’s work on reactionaries, radicals, and academics and our enduring love of perversity arguments:

Indeed, perversity arguments are appealing not only to reactionaries and the left-of-liberal left but to academics, irregardless of ideology. As Hirschman says, a perversity argument “is, at first blush, a daring intellectual maneuver. The structure of the argument is admirably simple, whereas the claim being made is rather extreme.” Perversity arguments are counter-intuitive, attention-grabbing. These are attractive characteristics for someone trying to stand out in a crowd of monographs. And sure enough, the attack on liberalism as perversely harming the disempowered has become quite fashionable in criminal justice in particular. Bill Stuntz is its most well-known (and least radical) author, but structurally similar claims have sprouted up all over, usually from the far left. These are arguments that prison conditions litigation causes an increase in incarceration, Miranda rights cause increased arrests, and so on. The claims are empirical—A caused B—but the arguments are usually a combination of ideological and hypothetical.

Perversity arguments feel smart and daring. They make you feel like you’ve seen a secret truth. But they also work to disempower and disengage. They paralyze us with fear, uncertainty, and doubt. Every step in the minefield of unintended consequences and backlashes is probably doomed, so the only safe thing to do is stand still. From the perspective of perversity helping hurts, loving hates, attacking strengthens, and truth-seekers lie. Nothing is what it seems, and everything must be viewed through a hermeneutics of suspicion that ends with a kind of paralysis or status quo preference.

But at the same time… sometimes everything is not what it seems. Sometimes our well-intentioned efforts do make things worse. If Forman is right, DC’s leaders were facing real crime problems in need of real solutions, and they built a tidy mass incarcerated city without ever seeking to do so. And his chapters on DC’s responses to gun violence, especially, strike me as importantly relevant to current discussions of gun control in the wake of the Parkland shootings.

Leave a Reply